Report on the 2019 General Election

A Note on Publication

Democracy Club usually reports annually, based on what we call the ‘election year’, which assumes that there are always scheduled elections at the beginning of May. However, with the 2020 local elections postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic, we have issued this report early to cover our work during the 2019 snap general election.

Executive Summary

This report outlines Democracy Club’s work and its measurable effects during the 2019 UK general election. Notable achievements during this period included:

- Processed four million postcode searches via WhereDoIVote.co.uk, WhoCanIVoteFor.co.uk, and our live data feed, three times our previous record.

- Successfully put our general election plan into action, employing six extra members of staff (including contractors).

- Achieved 73% polling station finder coverage for population of England/Wales/Scotland.

- Crowdsourced all parliamentary candidates within 24 hours of close of nominations.

- Achieved some major new data partnerships, notably seeing our candidates data used by The Guardian, The Times and Sky News.

- Links to our websites were shared online by major organisations of state, including the Electoral Commission and UK Parliament.

- Successfully developed and deployed a combined polling stations and candidates widget in time for the general election.

- Added Welsh language capability to both widgets.

- Gained over 1,300 new volunteer contributors to our candidates database.

We also experienced some disappointments:

- A substantial portion of our polling station coverage, including Liverpool, Sheffield, and much of Scotland, was added late (10 or 11 December), missing a lot of potential users, while our Welsh coverage was comparatively poor.

- Our results data operation was poorly organised, meaning that a small number of volunteers had to shoulder much of the overnight burden.

- Failed to convince any journalists or media organisations to report on the UK’s lack of digital democratic infrastructure.

- Google didn’t use our data, despite huge success in 2015

Introduction

The general election marked the high point of what was an extremely successful year for Democracy Club. In terms of user numbers, partnerships, data re-users and volunteers, December 2019 broke all of our previous records. We were trusted to provide impartial election information by an enormous range of organisations, including the Electoral Commission and local authorities; media outlets and charities; and, for the first time in our history, the UK Parliament.

This success was made possible through extensive planning for a ‘snap’ general election, which we put in place at the start of the year, plus the experience gained from working in the rapidly moving environment provided by the 2019 local and European elections. Upon the announcement of the general election, we were immediately able to hire the necessary staff (including, for the first time, a dedicated partnerships manager); put out a call for polling station data with the Electoral Commission; and assist our crowdsourcing volunteers with collecting more information on general election candidates than ever before. Our thanks, to all those who made this possible are recorded in the acknowledgements.

Sym, Will and Peter

Evaluating Overall Reach and Impact

In terms of our organisational goals for 2019-2020, our measurable ambition for a snap general election was to reach ten million people ‘with voter information’. This was an extremely ambitious target, complicated by the fact that we are unable to track how organisations make use of our candidate data downloads.

Nevertheless, what we do know suggests that we came relatively close to achieving this goal. The number of direct users of Democracy Club’s services was at least three times larger than at any previous election: between dissolution of parliament and election day itself, our database processed around four million postcode searches, including 800,000 via the website of the Electoral Commission. Meanwhile, our candidate data powered stories and tools on websites with a combined reach of millions, including The Guardian, The Times, and Sky News; regional news websites like Cambridgeshire Live; and social media accounts such as Britain Elects. Combined, all of these stories and tools undoubtedly received more than ten million views.

We are particularly pleased to note that all this was achieved within a very small time frame. Building on our success during the European Elections, it is clear that Democracy Club is now firmly established in the minds of journalists and, increasingly, communications staff in local and national government, as the go-to source for reliable, impartial voter information.

The Election in Data

Polling Locations Data

Coverage

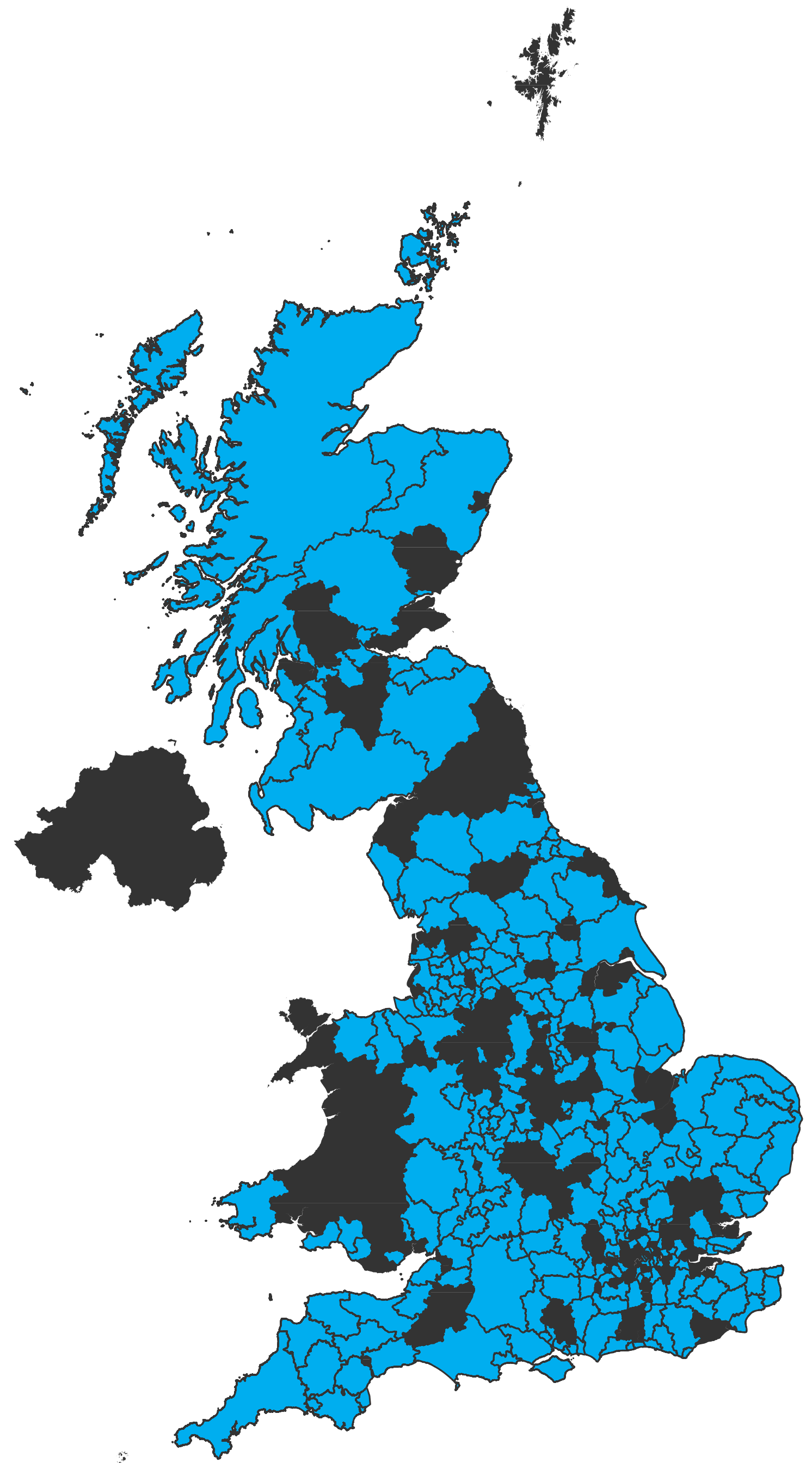

The 2019 general election was the first ‘snap’ election which our polling data service has had to approach from a standing start: both the 2017 general election and the 2019 European election were preceded by local elections which provided a base to work from. Consequently, this winter we cautiously estimated that we might be able to collect data from 40-50% of UK councils in the six weeks to polling day.

However, we are delighted to say that we considerably exceeded these expectations. Of the 371 councils in England, Scotland and Wales (we do not cover Northern Ireland), we collected polling station data for 266, covering 73% of the voting age population. This is our highest ever UK-wide coverage, and represents a good increase on the EU vote (58%). Within the constituent nations, our general election coverage breaks down as follows:

| Nation | Coverage (% Voting Age Population) |

|---|---|

| England | 75% |

| Scotland | 73% |

| Wales | 50% |

Some caveats should be added to these headline figures. A number of councils, including Sheffield, Liverpool and the majority of Scotland, were only added on December 10th, with the result that tens of thousands of users were served with a ‘no data’ message in the days running up to the election. Despite communicating with the council, we were also unable to add Bristol.

The Welsh figure, although poor, nevertheless represents a doubling of our coverage from the EU elections, when only five councils answered our call. Wales is the only part of the UK which has seen little to no growth in polling station coverage since 2016, and it is clear that, along with Scotland, this is an area we should focus on for 2021, especially in light of the approaching Senedd elections.

In the case of Scotland, a lack of communication from Scottish councils, combined with the uncertain state of the open data provided by SpatialHub.scot (a source we had found to be out of date during the European elections), led to considerable delays. We eventually solved the issue by using volunteers to manually compare the Spatial Hub data with the published situation of polling stations documents. However, this answer was implemented late, only after failing in our attempts to get in touch with Scottish councils, and still resulted in our having to throw away a lot of data. It is clear that, with the approach of the Scottish parliament elections in 2021, a more methodical and multi-pronged approach is required - attempting to build links with individual councils while also setting the crowdsourcing volunteers to work earlier.

Reach and Users

Between Monday, 9 December and Thursday, 12 December, our polling stations database handled 3.5 million postcode searches. This is the highest amount of traffic we have ever experienced, almost three times more than during the European elections. In addition to WhereDoIVote.co.uk, our polling station data was accessed across the following platforms (rounded to the nearest thousand):

| Source | Searches |

|---|---|

| WhoCanIVoteFor.co.uk | 629,000 |

| tactical.vote | 480,000 |

| Electoral Commission | 320,000 |

| Labour Party polling station finder | 164,000 |

| Democracy Club Widget | 108,000 |

| votesavvy.co.uk | 18,000 |

| Ready10.media (JustPark.com) | 7,000 |

| Others | 19,000 |

Our biggest user over the course of the entire campaign was the Electoral Commission, who processed 800,000 searches.

Although these numbers are considerable, once again we were unable to convince any social media company or news organisation to build their own tool using our online open data feed (our ‘API’), relying instead on direct linking to WhereDoIVote.co.uk.

Labour was the only political party to use our polling station data, although it was open to everyone. WhereDoIVote.co.uk was separately shared and used by a number of other political parties (see below), while the Liberal Democrats built their own polling station finder, although we do not believe this received traffic comparable to our own. In response to this situation, we put out a call for a discussion about polling data provision on the day of the election.

Analysis

For many councils, the Democracy Club polling station finder has become an integral part of their electoral communications, and we have established relationships with the vast majority of local authorities. Of English and Welsh councils, only sixty-one (18%) did not send us data during any of 2019’s elections, and we were on course to reduce this number even further before the postponement of 2020’s local elections.

However, the high coverage achieved during the 2019 general election was in part due to fortuitous circumstances, as we were able to utilise the infrastructure, experience and contacts we had built up during the year and which may not exist in 2021, for example. We were also put under great pressure, with the result that many councils did not go online until the last moment (including one on polling day itself). It is clear that in the case of a future snap election, we would struggle to replicate these results without significant prior preparation or outside support.

Going Forward

After the breakneck pace of elections in the last couple of years, we are taking advantage of the relative lull to make some improvements behind the scenes to the polling stations finder. We’re adapting our data model to allow us to serve an answer to users who live in postcodes which are split between different local authorities.

To do this we are embracing Unique Property Reference Numbers (UPRNs), which will allow us to tie together lookups between WhoCanIVoteFor and WhereDoIVote in postcodes split across constituency boundaries.

This decision came at a similar time to the announcement that UPRNs would become part of Ordnance Survey’s open data offering, we hope this will open other avenues for linking our data.

Focusing more on the ‘R’ and less on the ‘D’, we are planning a research program with councils on data quality issues. We want to learn more about how we can best feedback on data quality issues that we discover. We also want to find out more about when and how those issues get into the data, to potentially improve how we look for and correct them.

Candidates Data

Although widely anticipated, the prospect of a snap general election posed problems for Democracy Club’s Candidates database. This is because candidates.democracyclub.org.uk can only handle elections which have a scheduled date, which the general election only received at the start of November. Therefore, as a workaround before the date had been decided, we created a Prospective Parliamentary Candidate spreadsheet to collect details of individuals who had already declared their intention to stand. The response from our volunteers was excellent, with the result that we were able to immediately import 1,583 candidates into our system at the moment of parliament’s dissolution, although some of these (especially Brexit Party) will have been removed upon publication of nominations.

This momentum carried over to nomination day (14 November), when our volunteers crowdsourced and verified all 3,320 parliamentary candidates within 24 hours: the only delays encountered were caused by a small number of late-publishing councils. Encouragingly, this dataset contained only a tiny number of errors (quickly rectified), comparable with the list produced by the Press Association, who completed their compilation well after Democracy Club.

We are pleased to say that by polling day itself, our detail on individual parliamentary candidates was also high:

| Data field | Candidate coverage |

|---|---|

| Profile Picture | 97% |

| Email Address | 86% |

| Personal or PPC Website | 74% |

| Twitter handle | 82% |

| Facebook Page (personal or campaign) | 68% |

| Statement to Voters | 36% |

| Favourite Biscuit | 10% |

Comparing this coverage with the data we acquired during the 2017 general election, we find that most fields saw little change. Our Twitter and Facebook coverage both increased by 12% and 9% respectively, although this may be because more candidates are now on social media. Statements to voters, which are out of date as soon as the election is over, always present a challenge, something which is reflected in the fact that our coverage in 2019 was little different from the 34% achieved during the 2017 election.

Reach and Users

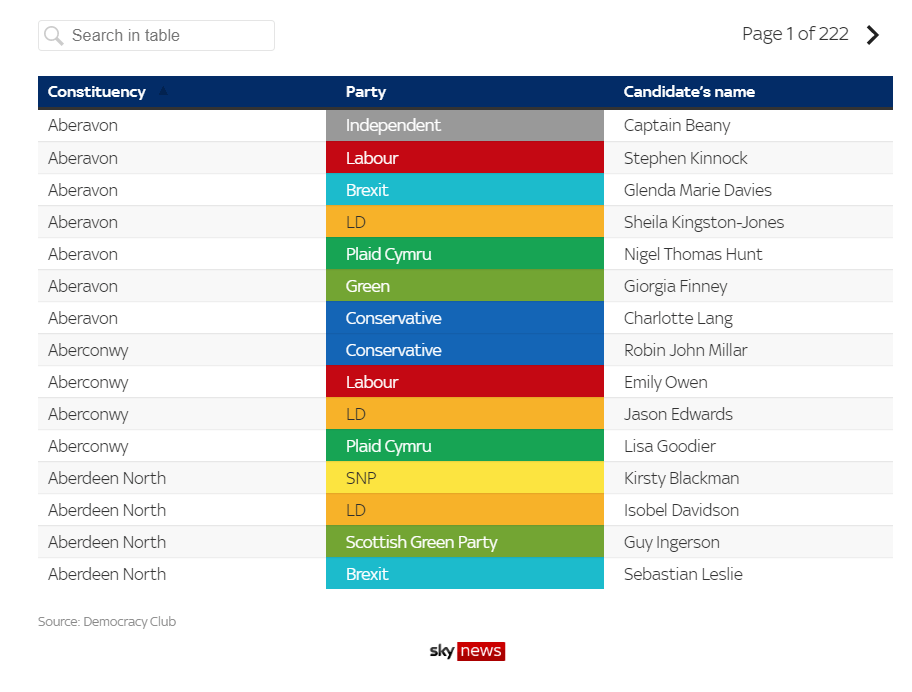

The 2019 general election represented a significant success story for Democracy Club’s candidate database. Not only was our live data feed (API) used by our regular partners - notably the Electoral Commission and In Your Area - but our candidate datafile download (provided in CSV format) also powered look-up tools on the websites of The Guardian and Times newspapers, and Sky News. Anecdotally, we also know that our CSV was used by a number of charities and other bodies to run campaigns emailing candidates.

Our candidate data also inspired stories across local and national media, especially during the period immediately after nomination day when a number of outlets used our numbers to report on the number of Brexit party candidates. Most notably, The Times used our CSV to analyse the gender of candidates, resulting in a 16 November story in the print and online paper, which was widely circulated among other newspapers.

Analysis

The strength of Democracy Club’s database lies in the speed, accuracy and openness with which it is constructed. Its widespread use by media organisations, in preference to other commercially available candidate lists, reflects this. On the other hand, speed and openness can have its problems. Because a one-time anonymous CSV download remains the most popular way for organisations to access our data (rather than our live online feed), we are unable to alert users to subsequent corrections. For example, a small, initial error in the number of Brexit party candidates continued to circulate in the media long after we had corrected it on our site.

This election demonstrated the extent to which our task has shifted from simply building a database, to one of maintenance. Because a large proportion of our candidate contact details are now carried over from previous elections, the amount of work required to keep these relevant and up-to-date is now considerable. It is also becoming clear that this is a task which requires a shift in focus on the part of our volunteers themselves. The majority of our contributors usually focus on adding information to blank candidate profiles, a task which is very useful, but which can have the effect of missing candidates whose situation has changed. In this respect, 2019 presented a unique challenge, due to the considerable number of MPs standing for new parties or as independants, or ex-MEP candidates running with new social media accounts. At times we struggled to keep up with these developments, and in one or two cases (e.g. Independent Group for Change Candidates), we were displaying incorrect information well into the campaign period.

Database maintenance is an area which will only grow in importance as we move into the 2020s. Because Democracy Club first started covering local elections in 2016, and because councils elect in four-year cycles, the postponed 2020 and 2021 local elections will present the same problems as the general election did, but on a much larger scale. In the long-term, we may need to think about the overall structure of our database model, and consider moving towards separating candidacies from candidates, for example.

Nevertheless, our low error report rate suggests that, for the time being, our database continues to keep a high level of accuracy. We remain confident that Democracy Club continues to offer a level of detail on UK election candidates which is unmatched anywhere else.

Results data

During the night of the general election Democracy Club volunteers recorded the results as they came in, and we had a full record by the next morning. However, our operations in this regard were not as well organised as they might have been, with one or two individuals shouldering much of the burden: this is something we must reflect on and plan for in future elections.

Reach and Users

We presented the election results on the relevant pages of WhoCanIVoteFor.co.uk, as well as an overall projection on the front page. Between 13 and 15 December, WCIVF received over 60,000 visitors, the vast majority of which we assume were looking for results.

Our key partner in this area was the data visualisation company Flourish, who created a fantastic range of maps and graphs depicting the results.

These visualisations were featured on a number of websites, including The Independent, The Sun, Wall Street Journal and The Scotsman. Flourish estimates these were viewed over ten million times during and after the election.

As election winners are marked as such in our candidates CSV, we also assume a small number of other users in the charity sector and elsewhere. For example, mySociety’s TheyWorkForYou.com used the data to create its list of new MPs immediately following the election.

The Election in Apps

‘Apps’ refer to the services we run using our data: the websites WhereDoIVote.co.uk and WhoCanIVoteFor.co.uk, and our related polling station and election widgets.

The general election represented a major success for Democracy Club’s partnership work, which was significantly boosted through the efforts of a specially recruited partnerships manager.

Democracy Club worked with four major social media platforms - Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Snapchat - to deliver WhereDoIVote.co.uk to as many UK users as possible, gaining millions of site visitors before and during polling day. We also worked with a number of universities and student unions, and websites as diverse as Mumsnet, GRM daily, and Money Saving Expert, each of whom provided links to both of our websites via announcements and emails to their users.

Links to our services were also hosted in stories from almost all national and many regional and local newspapers. This built upon the good coverage we had already received during the local and European elections, and demonstrated that Democracy Club websites are now a standard resource for journalists looking to populate articles about UK elections.

As a consequence of this success, Google Analytics traffic to WhereDoIVote.co.uk and WhoCanIVoteFor.co.uk, combined with Widget use, totalled almost four million over the entire election period from 6 November (dissolution of parliament) to 13 December (results day).

WhereDoIVote.co.uk

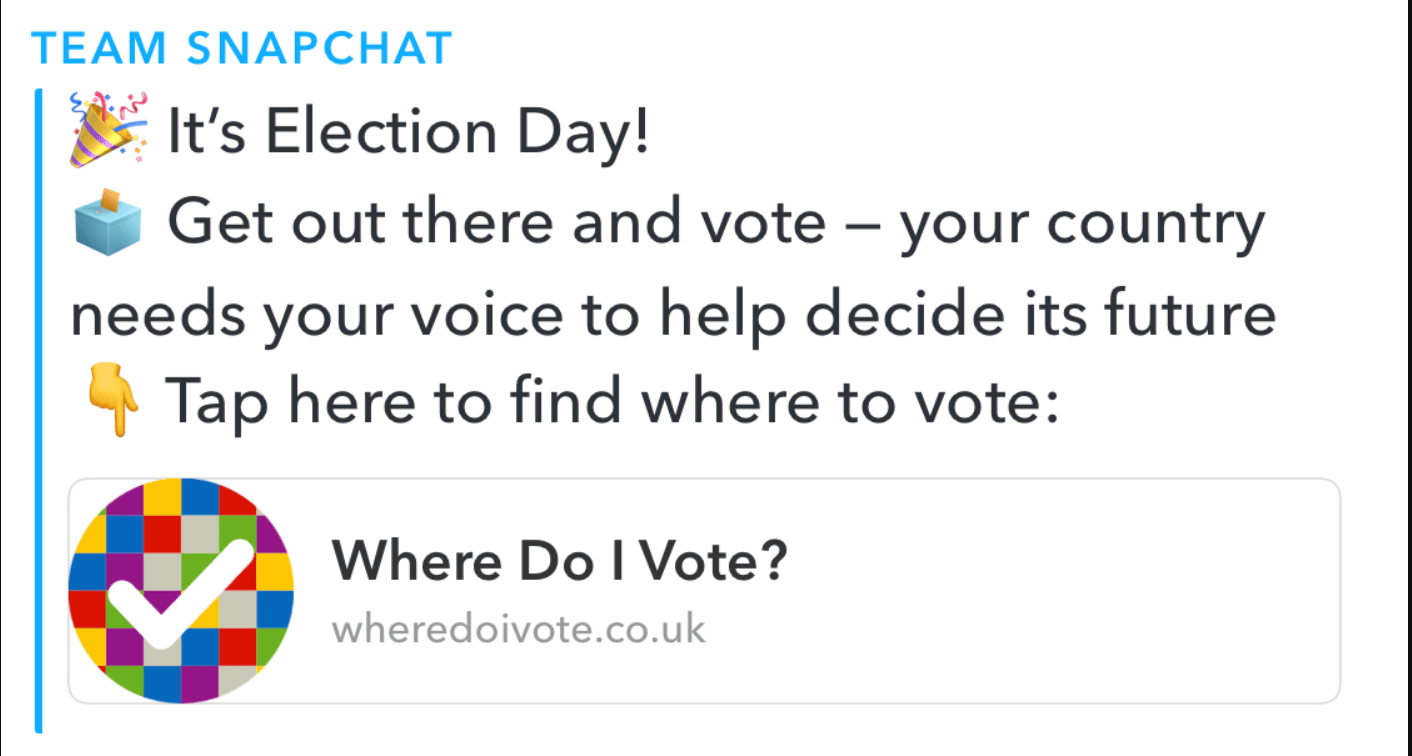

The general election was an enormous success for the reach of WhereDoIVote.co.uk. Most notably, this election saw us continue our partnerships with Facebook and Twitter, while also branching out to Instagram and Snapchat. Social media giants are increasingly adopting more responsible and active positions on civic engagement, and it is clear that they view Democracy Club’s polling station finder as a useful and non-partisan way of engaging their users during election periods. As far as we are aware, Democracy Club is the only UK company to have worked directly with the four largest social media platforms in this way.

-

Snapchat sent a message to all of its UK users of voting age -

Facebook placed a prompt in the timeline of every UK user -

Twitter placed a link in the feed of every UK user -

Instagram created a special sticker

-

In an effort to combat political disinformation on their platform, Twitter placed a link in the feed of every UK user during the four days prior to the election, which received 170,000 clicks (the head of public policy at Twitter gave evidence to the Lords committee on digital democracy earlier this year)

-

Facebook placed a prompt in the timeline of every UK user on election day itself, directing almost 800,000 visitors to our site.

-

As part of their civic engagement efforts, Snapchat created a unique lens and filter linking to WDIV, and also sent a message to every person of voting age in the UK on election day, providing us with almost four hundred thousand visitors in the run up to the election.

-

Instagram created a special sticker linking to the ‘official election information’ at WDIV, providing us with another 870,000 visitors. This sticker, the first the company has created for a UK election, was used by a wide range of influential accounts, as well as the central party accounts of the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats.

Elsewhere, The Guardian hosted a prominent link to WDIV on its front page throughout polling day, while a wide range of other media organisations, directed users to it via news articles or liveblogs. The site was shared widely by individuals across social media, not least by politicians (some prominent Labour and Liberal Democrat MPs shared links in preference to their own parties’ finders). Our work communicating with students unions and other organisations was well rewarded with a wide range of communications, including internal emails sent to students. Last but not least, WDIV’s widespread inclusion in council communications once again demonstrated how crucial our service is for electoral services teams.

The effect of all this activity on our traffic was marked. In total, according to Google Analytics, three million people visited WhereDoIVote.co.uk between 6 November and 13 December, 97% in the final four days. This figure is almost three times greater than any previous election.

However, such success brought new problems: WhereDoIVote.co.uk experienced a high ‘bounce’ rate - that is, people who reached the site, but immediately left without engaging. This is unsurprising considering that much of our traffic reached us via social media (70% of Instagram referrals did not put in their postcode, for example). Similarly, although our user feedback shows a satisfaction rate of 90%, the written feedback offers a more mixed picture, with some users noting that they were too young to vote, or complaining ‘this is not what Snapchat is about’. Most of these issues are beyond our control, but it may be that in the future we could reflect more on how different users reach our services, and whether we need to tailor our landing page to reflect this. Read more on our WDIV feedback.

Broadly speaking, although we are happy with our partnership work, our ideal scenario is one in which the social media giants use our polling station data to build their own tools, rather than linking to WDIV. We suspect that the high bounce rate is in part due to the fact that many people were not expecting to be redirected to an external website. We will continue to try to convince our media partners to use our live data feed in the future, although we recognise that the likelihood of this happening is relatively low.

WhoCanIVoteFor.co.uk

WhoCanIVoteFor.co.uk ran smoothly throughout the general election campaign, with few technical issues, and received an acceptable satisfaction rate from user feedback. The site was widely shared online (although received little to no coverage in its own right), and accumulated its largest-ever number of users. We are proud to say that our services are trusted not only by journalists and charities, but also by local authorities, the Electoral Commission, and parliament itself.

In addition to the information collected in our candidates database, we worked hard to provide users with as much extra information as possible. Most importantly, we provided links to the manifestoes of almost all parties standing two or more candidates. We also imported biographical data from Nesta’s 2017 database, Companies House information, and the Facebook advertising library. However, these last three data sources were found to contain some errors and resulted in a small number of complaints and requests to amend or take-down information: it is clear that we should take care to arrange more methodical checks when using this information in the future.

Reach

Building on the EU elections - when WhoCanIVoteFor.co.uk was featured in a number of stories by national newspapers - the general election marked a significant breakthrough for media coverage of this service. Starting immediately after the dissolution of parliament, WCIVF was linked to in stories from The Sun, The Metro, The Mirror, The Express, the Evening Standard and The Telegraph, the last of which hosted dozens of links and alone provided 15,000 referrals.

Even more encouragingly, a link to the site was placed on the website of the UK parliament, offered up to users of the Electoral Commission’s voter information pages, and placed in a banner on the homepage of the largest local authority in the country, Birmingham City Council. The social media accounts of Parliament, the Commons, and a number of councils all shared links to WCIVF multiple times throughout the election period.

Nevertheless, a bare majority (51%) of WCIVF users reach the site by searching online, indicating that we are now well positioned for search engine optimisation.

As indicated above, WhoCanIVoteFor.co.uk saw 629,000 postcode searches between 9 and 12 December - our highest-ever user numbers. This translates into 405,000 unique visitors over the four days - almost as many as the entire period from January to June 2019. In total, Google Analytics reports 864,000 people visited WhoCanIVoteFor.co.uk between 6 November and 13 December.

Between the close of nominations on 14 November and election day on 12 December, we received 13,386 pieces of feedback on WCIVF, of which 53% were positive - an approval rate slightly up on the European elections, and a very good result compared to longer-term trends. Read more on this feedback.

Widgets

In the months before the general election campaign we considerably improved our embeddable polling station finder. In terms of accessibility, we implemented a number of small redesigns to better meet WCAG2.1 accessibility requirements, and also added a Welsh language option. Additionally, we also rolled out a new ‘elections’ widget, providing candidate details and, where available, polling stations.

Reach

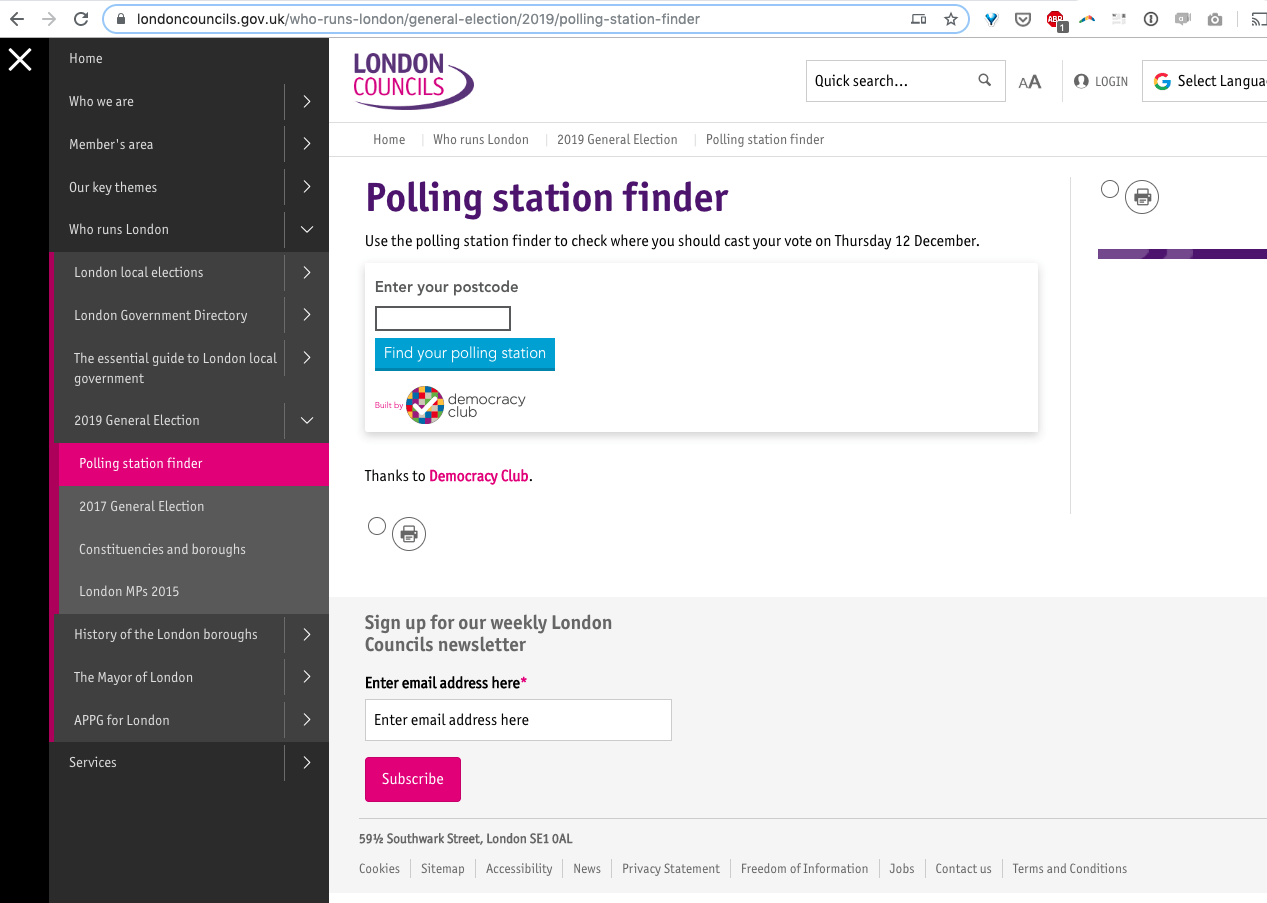

During the election our widgets were embedded on 145 pages across almost a hundred different websites, receiving 108,000 searches in the final four days of the campaign alone. These included local authorities, newspapers (e.g. Manchester Evening News), londoncouncils.gov.uk, and the website of Plaid Cymru (sadly, the party did not make use of our Welsh language toggle, although a number of Welsh councils did). As in previous elections, we received high praise from council elections officers, many of whom would otherwise be unable to provide voters with a polling station look-up on their own websites.

Volunteers and The Club

The Democracy ‘Club’ continues to grow. Our Slack group contains 630 people and was very busy during the election campaign. Between the start of November and 12 December, candidates.democracyclub.org.uk acquired 1,306 new users - more than signed up during the whole of the period covered by our last report. Measuring the number of edits is difficult due to our use of bots to apply changes suggested by humans (e.g. our ‘candidatebot’ racked up hundreds of edits by importing the prospective candidate spreadsheet put together by our volunteers prior to the announcement of the election). Nevertheless, we know that the site saw 36,769 edits over this time period, of which 18,752 were directly contributed by a human.

We did not host any events to mark nominations day this year (‘SoPN parties’), as the small number of documents available to crowdsourse did not necessitate it. A small event held in London after nominations closed attracted few attendees.

Finance and Governance

Finance

Unfortunately, we failed to raise any extra grant funding for a snap election. This was partly because, despite it being predictable for months before being called, it’s hard to fundraise for something that’s not currently planned.

At the point the election was called, we might have been able to raise some funds, for example via a crowdfunder, but the tight schedule and extra work would have made this hard. It also wasn’t clear that we would have been able to make good use of the extra funds.

The Electoral Commission paid us for the provision and support of our data feeds to them.

We are delighted to say that we have secured a new funder in the form of Luminate,, who are supporting our work on future planning and what we might do beyond the electoral cycle. We have also recently been announced as a beneficiary of Nesta’s 2020 ‘Democracy Pioneers’ fund.

You can see all funding over £5,000 on our funding page.

Governance

In 2019 Rebecca Eligon and Alison Walters both stepped down from the board. We thank them both for their thoughtful hard work. We think a slightly smaller board is more helpful, so we have decided not to directly replace them.

After the General Election both Joe Mitchell and Chris Shaw decided to leave Democracy Club. This has serious impacts on the future of the organisation, as they formed two thirds of the core team. It’s hard to sum up how much each of their work contributed to the organisation over the last few years. The success outlined in this and other reports is mostly thanks to them.

Looking forward, Democracy Club now has a smaller team and no elections in 2020. This allows room for a reset and a rethink. The initial plan was to keen an organisation going long enough to excel at delivering open data, tools and services for voters at the 2020 General Election. We could never have anticipated the situation we find ourselves in, but would like to think that our overarching goal would have been met, had we had a few quiet years to plan for a scheduled general election.

We expect to spend the rest of this year resting and slowly gearing up for a large and complex set of elections in 2021. More on these plans to follow in the next few weeks.

Acknowledgements

Once again, we must acknowledge the excellent work of Democracy Club’s volunteers, many of whom contributed hundreds of individual edits. Special thanks also to the small band of volunteers who stepped in at the last minute to help us check through the Scottish polling station data received through spatialhub.scot, thereby helping us to reach hundreds of thousands more voters than we otherwise would have managed.

Our thanks once again to the UK’s tireless electoral services teams, who remained a pleasure to deal with despite the trying circumstances of a December election. Our partners at the Electoral Commission continued to provide much-needed communications and other assistance.

We would also like to thank our other partners mentioned throughout this report. In particular the team at Flourish, especially Mark and Robin, for their contributions to our results database.

A final mention in dispatches must go to our partnerships officer Terry; and Alex, who stepped in to help with polling stations imports.

Appendix 1: By-elections 2019-2020

Between the end of the period covered by our last report (June 2019) and suspension of elections (16 March 2020), we covered 172 by-elections, including 35 on the day of the general election itself. These included two UK parliamentary elections, one Scottish parliamentary election, one Police and Crime Commissioner election and 168 principal council by-elections. We are confident that we covered 100% of all by-elections over this period, although the general election added strain to this process: one 12 December election was first identified by us as late as 9 December, a good illustration of the need for a centralised, official list of all UK elections.

The last by-election before suspension was held in Coventry on 16 March; three other elections on this date were cancelled. We continued to record all by-election cancellations as they were announced, displaying this information clearly to users of WhereDoIVote.co.uk and WhoCanIVoteFor.co.uk.

Appendix 2: Our work towards the 2020 local elections

Before the postponement of the local elections on 13 March, Democracy Club had agreed continuing partnerships with both the Electoral Commission and London Elects for the provision of polling station data (with the target, in the latter case, of 100% London coverage). By this date we had acquired data from 90 councils (26%), and were confident of exceeding our general election coverage. We had identified all council seats up for election, and had begun developing partnerships strategy, including relating to the Police and Crime Commissioner elections. We are now well prepared for the anticipated resumption of elections in 2021.